Amid growing discontent about the economy--corroborated by my impressionistic view based on Twitterati, most of whom are favorably disposed to the Modi government--a few prominent economists have come out strongly against any short-term fiscal boost. Some have predictably called for more "reforms." Let me state categorically, no amount of reforms will kickstart the private sector quickly. Corporate debt loads are still high, capacity utilization low, and banks are hobbled by NPAs. Businesses invest when they swamped with demand and credit is easily available. Of course, reforms help speed up investment when businesses are eager to invest, but they are a distinctly secondary condition. The famous 1991 reforms started soon after I joined ICICI in 1991. There was no magical pickup in capex. The new project pipeline was practically dry for the next several months. Capex did not meaningfully pickup until 1993-94.

Reforms mantra at this juncture is like the expansionary fiscal consolidation snake oil that was sold during the early stages of the European sovereign debt crisis. The idea was that government austerity and spending cutback could somehow be miraculously lead to faster economic growth. If this sounds too good to be true, it is. Essentially, it ignored the simple math of balance sheet constraints. if European governments were going to consolidate, that is run surpluses and bring down their debt, elementary accounting would imply that some other sector(s)--households, firms, or the rest of the world--had to run a corresponding financial deficit. Given the high levels of private sector debt in many of the beleaguered European countries at that time (excessive household debt among other things had caused the European crisis) and a global economy in which every country was bent on increasing its trade surplus, expansionary fiscal consolidation was an oxymoron.

India's situation is less parlous than Europe's in 2010-11, but to expect the corporate sector to lead to a robust acceleration in growth belies common sense. India's corporate debt-to-GDP appears low in comparison to some other countries (chart 1), but this is misleading. Ideally, corporate debt should be scaled to the sector's output. This data is not easily available for all countries. However, I do have it for the US. Although US corporate debt to GDP ratio is nearly 1.5 times India's, the corporate sector's share of GDP in the United States is close to twice that in India. And, US corporate debt is near records highs historically. Moreover, recent report from Thomson Reuters bears out the struggles of the corporate sector with debt. Unfortunately, there is no long history of India's corporate debt but BIS does publish total private nonfinancial sector debt, which includes households and corporates. The second chart shows total private sector debt to GDP. Household debt is about 10% of GDP today, so most of the sharp rise in the last decade reflects the runup in corporate sector debt. Today's indigestion is payback for the exuberance of the 2000s.

Meanwhile, capacity utilization is still low. In fact, L&T CFO in a recent interview said that he does not see a private sector recovery for two more years.

Tight Policy

Given India's faltering growth and weak capex, fiscal policy is simply too tight. In the past, when spending growth was as weak as it is now, the fiscal deficit was wider by about two percentage points of GDP, or about 3 lakh crores! I don't want to suggest that those policies were perfect and have to be emulated. Hardly. (India's policies have been often been procyclical--that is, the government has splurged when the going has been good instead of leaning against the wind. The second chart below shows government debt overlaid on private sector debt. You can see the tendency for both to rise together. Instead, the government should be playing a stabilizing role--cutting back deficits when the private economy is booming and supporting demand when the private sector is retrenching.) However, in the present situation, with the private economy faltering and government debt near two-decade lows, a dose of fiscal boost is what the economy needs.

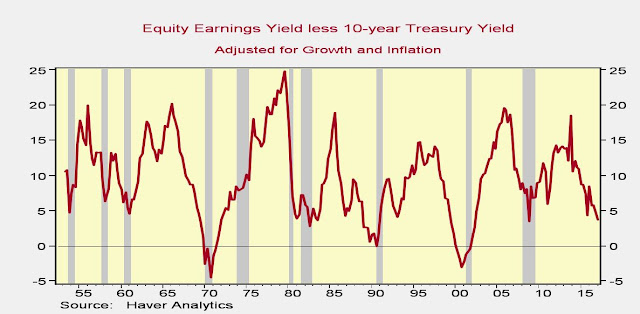

Not to be left behind, monetary policy is even more of a Scrooge. the spread between nominal GDP growth--which capture both inflation and real growth--and the RBI repo rate is near its lowest levels of the past 17 years, indicating that policy is tight. An easier monetary policy will spur household credit offtake--for consumer durables and housing. India's household debt is very low and household borrowing can help spur economic revival. Fiscal policy measures to support low-income housing combined with interest rate cuts can kill two birds with one stone.